Historical imagery is a valuable source of evidence for reconstructing the layout and evolution of buildings and landscapes over time – when used cautiously. In assessing the accuracy of representation, we must take into account the creator’s relationship with the site, his technical expertise, and motivation for the scene’s creation. A hand-drawn sketch that a ship captain made of a coastal castle in his journal on a trading voyage for future navigational purposes, for instance, is likely a closer rendition than a published engraving that a London-based printer produced, which may be a copy of another engraving, based solely on a textual description, or created to give the impression of British imperial might overseas. Past scholarship on the portrayal of European forts in African has highlighted the aspirational and perhaps exaggerated military representation of the Dutch, French, or British presence. Other researchers have, alternatively, interrogated visual portrayals of forts to understand the “architecture of enslavement.”

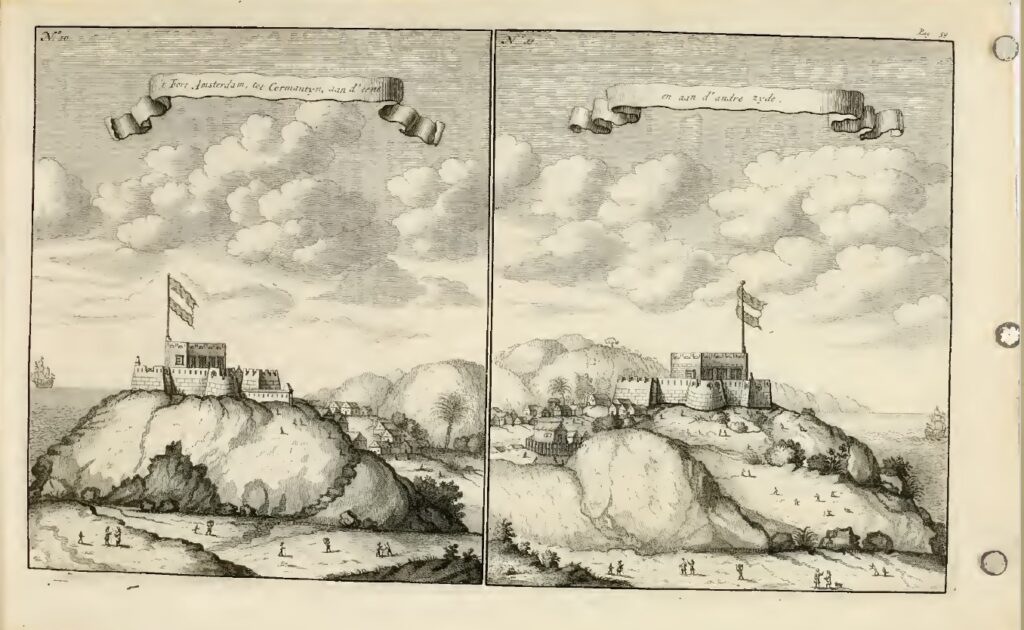

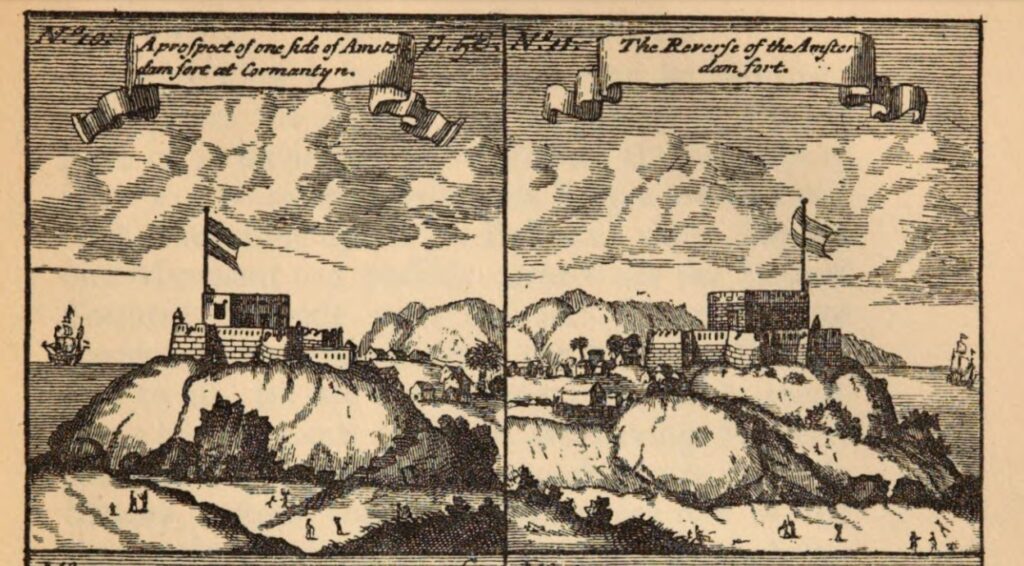

For the purposes of guiding future archaeological excavations and digitally reconstructing Cormantine Castle, Fort Amsterdam, and Kormantin’s landscape, we have brought together all extant sketches and engravings of the site and ordered them chronologically in order to create a contingent interpretive sequence for the hilltop fort site’s evolution alongside its surrounding town. Scholars A.W. Lawrence and Albert van Dantzig have previously attempted this, but used incomplete datasets or were less rigorous in considering the quality of the images they used.

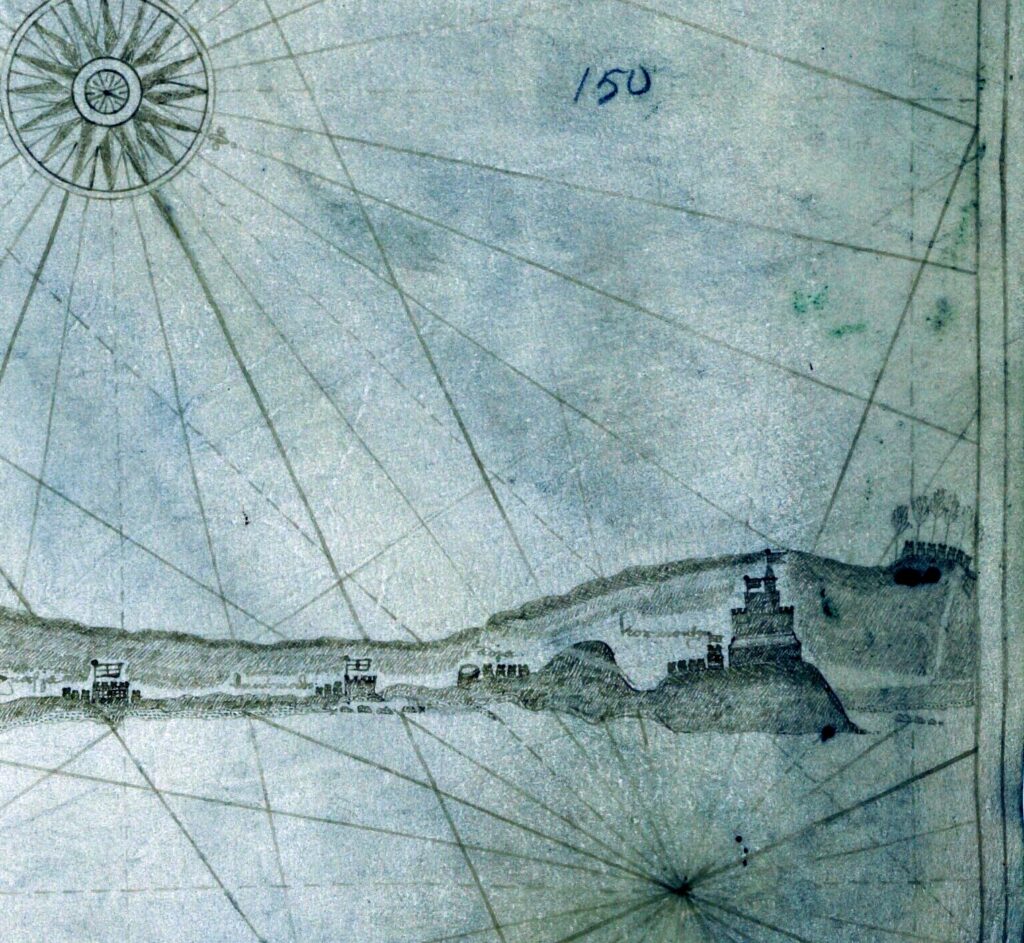

The earliest image of Kormantin dates to 1665, created during Admiral Michael de Ruyter’s expedition to capture all English forts on the Gold Coast. The original in the Dutch National Archive is a hand-drawn monochrome sketch of the Dutch invasion fleet and the coast between Cape Three Points and Cormantine Castle.

Although the forts and castles along the coast are stylized and out of scale, variations suggest that the icons reflect distinctive traits unique to each site. Cormantine Castle is accurately placed atop a promontory in front of a cove and with the inland hilltop town of Great Kormantin in the background. The castle’s Krom, or adjoining town, lies to the west.

The castle appears to have a two-story inner keep surrounded by a crenelated battery and with a taller tower in the northeastern or southeastern corner topped with a spired roof. A small detached battery lies to the castle’s west – an outer defensive work that is consistent with eyewitness accounts of the 1665 attack on the site.

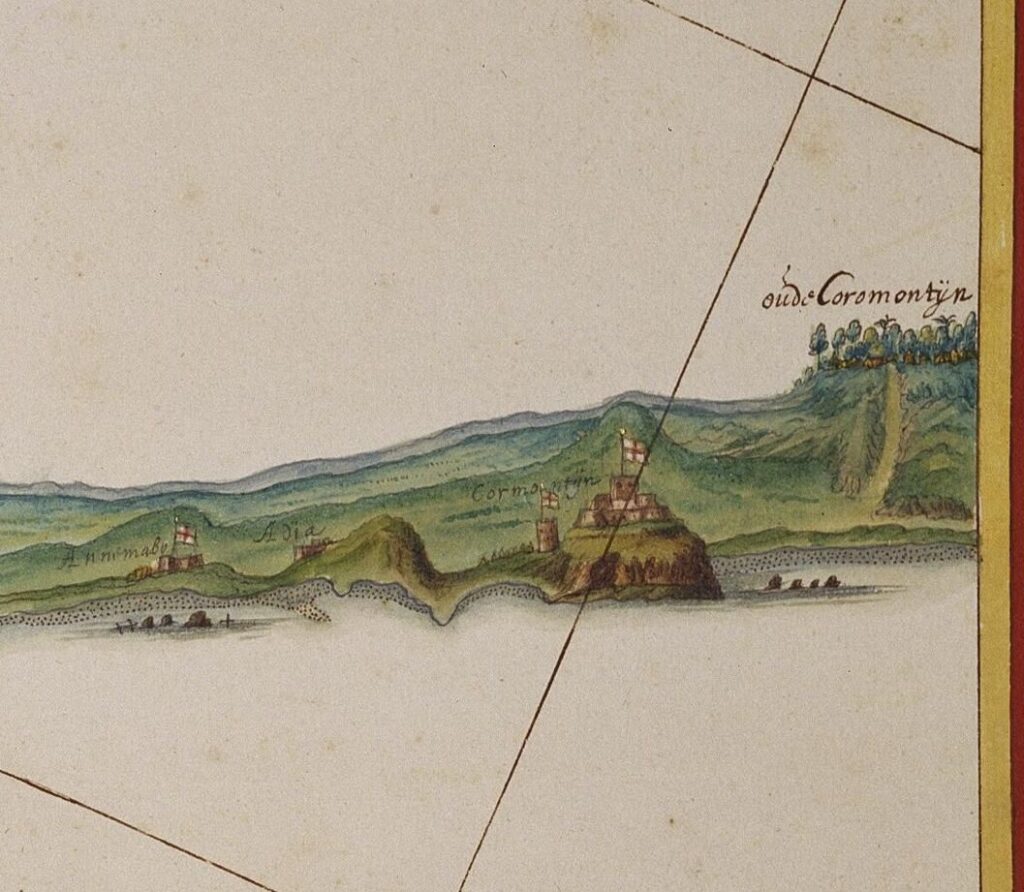

Dutch East India Company cartographer Johannes Vingboons created a colored copy of the original De Ruyter sketch and included it in his atlas. The Vingboons sketch provides richer detail, including the English flag of St. George flying atop the castle and tower, a lower profile of the castle’s interior keep, bastions on the castle’s corners, a flat rather than spired top to the tower, and a centered positioning of the keep tower. These are apparently the only two representations of English Castle Cormantine.

Within a few years of De Ruyter’s expedition, an unknown Dutch engraver produced three images of his fleet alongside Cormantine and Goree, his two most notable conquests, under the title Gezicht op Elmina, Cormantijn en het eiland Goeree Leaf with three performances July 1665. The upper image portrays the Dutch fleet under Admiral Michiel de Ruyter taking three captured English ships to anchor at Elmina.

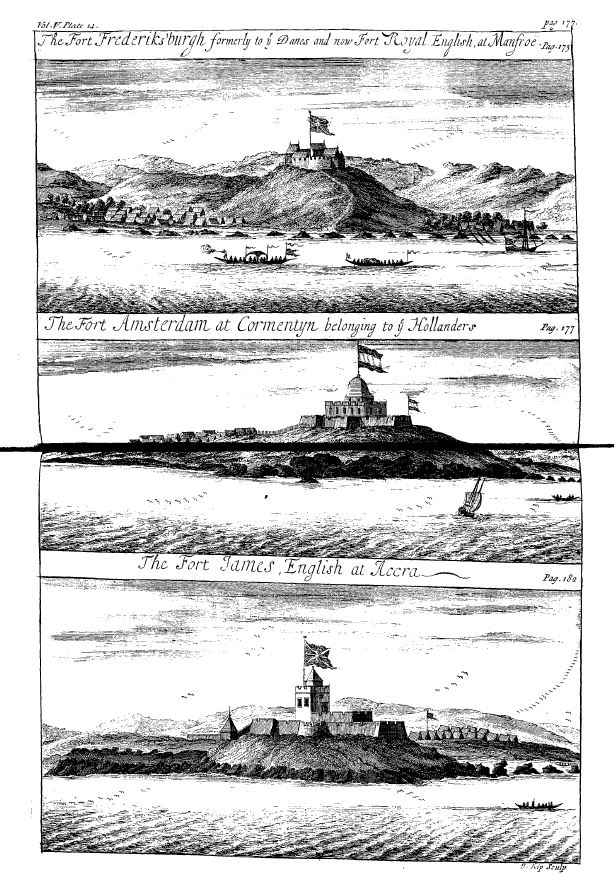

German author Olfert Dapper included a similar but larger and more embellished engraving of “The Castle Cormantine” in his 1668 Description of Africa inset among his descriptions of Dutch and English bases along the Gold Coast. The source for both the anonymous engraver and Dapper’s sketch is not stated and it is also unclear which of these similar engravings came first. Dapper’s Dutch subtitle suggests that the West India Company’s rechristening of the site as Fort Amsterdam had not yet occurred or circulated widely. (Dapper, Naukeurige Befchrijvinge AFRIKAÈNSCHE gewesten VAN Egypten, Barbaryen , Libyen , Biledulgerid, Negroslant, Guinea, Ethiopiën» Abyfïïnie (Amsterdam, 1668), 449.)

Kormantin’s layout agrees with the De Ruyter view but presents a more realistic landscape, suggesting it was based on the sketch of an actual visitor situated about half a mile offshore.

Dapper’s “Castle Cormantine” closely resembles Johannes Vingboons’ sketch in presenting a centrally located (although spire-roofed) keep tower flanked by four round bastions, and an extensive lower battery, albeit without crenelations. In the Dapper engraving, the standalone tower to the west is square in form, with crenelations. The steep cliff to the fort’s south sloping down to a western access beach closely matches the site’s actual topography. An identical engraving was published two years later in John Ogilby’s Africa, being an accurate description of the regions of Ægypt, Barbary, Lybia, and Billedulgerid, the land of Negroes, Guinee, Æthiopia, and the Abyssines, with all the adjacent islands (London, 1670), an extensively plagiarized uncredited English translation of Dapper’s work.

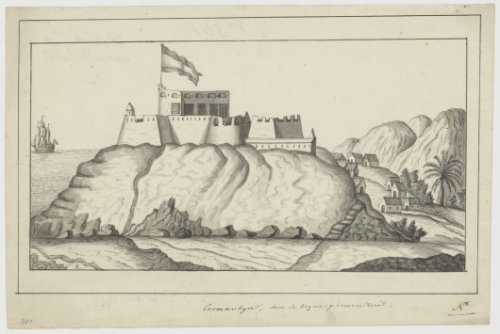

An undated engraving of Castle Cormantine made by an unknown publisher is included in a bound volume “Maps and views of various parts of the West Coast of Africa,” in the British Library (Add. Mss. 33976, formerly designated MAPS C22.bb10) along with all of John Ogilvy’s 1670 engravings. The view is noteworthy in showing the fort in an apparently damaged state and also labeling it “Fort Amsterdam.”

The title and Dutch flag in an enlarged image of the fort establishes that the portray post-dates 1665, but the tall central keep that dominates other engravings is missing, or represented only by two round towers whose upper works appear to be in ruins. It should be noted that both the 1665 De Ruyter sketch map and the c. 1668 Offert engraving portray the inner keep as having round towers, but whereas the Offert engraving presents the fort as having a flat faceted southwestern bastion, this sketch shows a round tower (an imperfection in the engraved surface unfortunately somewhat obstructs this particular example). The lower battery encloses three buildings whose gabled roofs peep over the curtain wall. It is somewhat difficult to reconcile this view with its near-contemporaries; if both are accurate, perhaps the damaged earlier English keep shown in the dated 1665-1668 sketches collapsed, leaving only two of its round towers standing. Dated sketches from 1679 (see below) onward include a tall inner keep but with square corner towers.

French slave trader Jean Barbot made two voyages to the Gold Coast in 1679 and 1682 and made numerous sketches of West African fortifications and coastal views. His original 1679 journal and a later copy revised to include his 1682 observations survive in the British Library and British National Archive, respectively. Barbot’s “Journal of a Voyage to Guinea, 1678-1679″ (Add. Mss. 28788) includes a hand-drawn sketch of Fort Amsterdam, which he personally visited as the Dutch commander was preparing to make extensive repairs and modifications.

Barbot’s sketch differs from the Dapper/Ogilby view in numerous ways, which may reflect a more accurate representation of the fort or may document changes that had occurred since the English castle had been captured. The earlier detached defensive tower is no longer standing, but an apparently wooden palisade wall had been constructed along the cliff edge to hinder an attack from the west. The sketch is unique in showing the fort’s western side (most are seaward views perpendicular to the southern curtain wall) and includes details unknown to previous scholars. Barbot’s interior keep has square towers with crenelated tops, an entrance with a roof overhang in the keep’s southwestern corner, and a single-story flat-roofed entry porch in the northwestern corner. A two-story square standalone tower that is seemingly joined to the rest of the castle occupies the extreme northwest corner of the fort. Consistent with other engravings, Barbot includes a taller square tower in the keep’s northeastern corner, with a sloped hip roof. The faceted bastion in the fort’s southwestern corner has a small sentry box at its apex, a trait consistent with Elmina Castle and other Dutch forts of the period.

Where many Gold Coast images include vague stylized native canoes, Barbot draws a hybrid craft with a high prow rigged with stepped masts carrying square and lateen sails, flying a Dutch ensign – a rare visual portrayal of African coastal vessels that vitally supported West India Company commercial and military operations by shuttling personnel, trading goods, communications, and sometimes enslaved people between its forts.

Made after his second 1682 voyage, Jean Barbot’s revised sketch of Fort Amsterdam reflects two years of intensive repairs and construction, which brought the fort’s appearance to more closely resemble that of the earlier Dapper/Ogilby engraving. The perspective is apparently similar to his 1679 sketch but somewhat further out to sea and from a more southerly direction, roughly square on with the fort’s southwestern bastion. Whereas the older fort’s inner keep had distinctive flanking square towers in each corner, the post-1682 keep appears to be a uniform square building. The artist’s angle makes it unclear whether the tallest keep tower is central or still in the northeast corner, but it now has a cupola style roof. All three of the visible bastions are square or diamond shaped. As in his earlier sketch, African canoes in the foreground are shown with stepped masts and high prows, and a palisade wall still extends from the fort’s northwest corner.

When Barbot’s work was posthumously published in 1732, the illustrative engravings mirrored his 1688 journal sketch (p. 177) and Willem Bosman’s 1705 account (p. 446, below).

Willem Bosman served as a Dutch West India Company trader on the Gold Coast between 1688 and 1702. He arrived as a sixteen-year-old apprentice but through hard work, extensively studying local customs and languages, a willingness to serve and numerous Dutch African outposts, and his good luck in simply surviving in a notoriously deadly environment during the Komenda Wars he advanced to the rank of Opperkoopman (Chief Merchant) at Elmina Castle. Strong differences of opinion with WIC Director General William De La Palma led to Bosman’s recall back to the Netherlands in 1702. Two years later, Bosman published Nauwkeurige beschrijving van de Guinese Goud- Tand- en Slavekust (“An accurate description of the Guinean Gold-, Tooth- and Slave Coasts”) in his hometown, Utrecht. A somewhat imperfect English translation was published the following year in London as A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea, Divided into the Gold, the Slave, and the Ivory Coasts (London, 1705).

An anonymous hand-drawn sketch of Fort Amsterdam from the east found among Dutch West India Company records which closely matches the 1704 and 1705 published engraving may have been made by Bosman himself, before 1702.